My city is witnessing its annual constant downpour. I say annual, yet it has been a long while since summers in Bangalore have had days where stepping out of the house without an umbrella is criminal. The roads are flooded, the lakes are overflowing, fish are on the street. “Orange alert,” “yellow alert,” “red alert,” is being repeated on news channels in dizzying patterns. Menshinkai bhajjis or chilli pakoras are being fried and hot, hot, tea is being served.

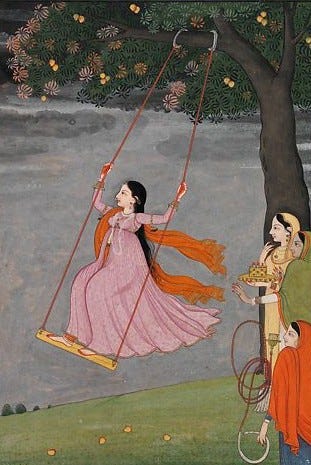

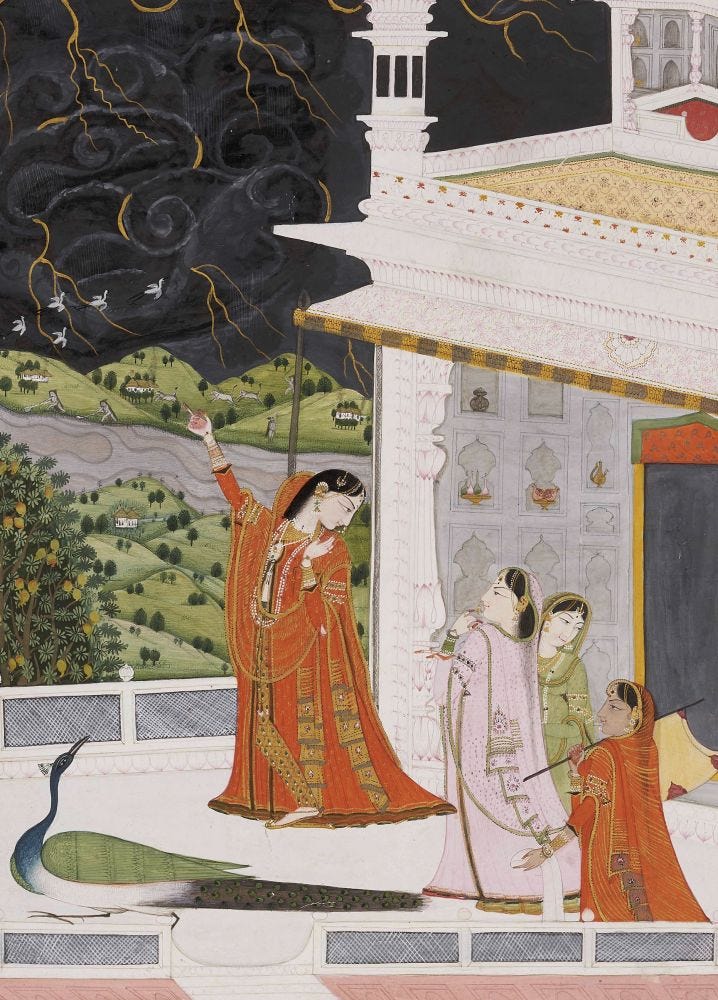

The monsoons punctuate the seasons in India. Arriving just after summer and leading us swiftly into an autumnal haze, the monsoon season often offers both respite and chaos. Currently, we are experiencing the latter. But it is often the prior that has led artists back to their art. Respite, the idea of satisfying that which cannot be attained.

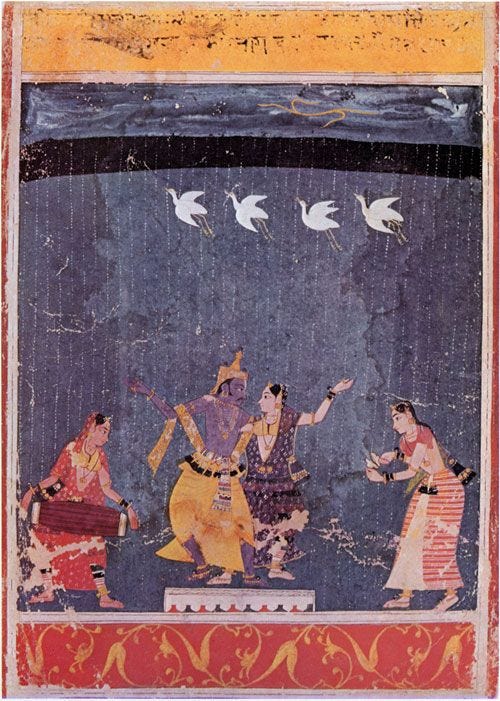

It is believed, in the classical arts, that a beautiful rendition of a song in Raag Malhar1, a melodic framework, can make it rain. The belief takes root in the 13th century when Tansen, the Sangeet Samrat2 of Akbar’s court, sang Raag Megh Malhar and made it pour. So evocative was his rendition of this monsoon raag that the clouds cried in applause. The sound of raindrops falling on metallic structures of gold and bronze come to mind, reverberating through the opulent court of King Akbar. Royalty felt respite that day.

Rain, the time for music

It is with a similar sound that Manna Dey’s Lapak Jhapak Tu Aa Re Badariya from Boot Polish, 1954, begins. A group of prisoners await the rain in their encampment when the lead singer, played by David Abraham, begins to sing. He is the conductor of this troupe of jesters who know of only one way to make it pour; to sing like Tansen. The first shot we see is of several bald heads which Abraham begins to play as if they were drums. He croons, “Lapak jhapak tu aa re badariya,” “Come and make it rain you large, grey rain clouds.” He motions to the bald heads of his fellow compatriots and says “sad ki kheti sookh rahi hai,” “the fields are drying up,” this land where no hair grows, this fertile land is now dry, come, make it rain.

His inmates chime in with a small upaj or rhythmic sequence in Teentaal3. They will continue to pepper his singing throughout the track, bringing up some interesting dynamics. In the song we see Abraham sitting on a higher platform than the others. The set up, him on a podium with the others sitting below him, might remind a viewer of a Hindustani Classical music class but the melodic interjections by the other prisoners might suggest a more Qawwali4 like feeling. It is common practice in a Qawwali presentation for members of the group to sing taans or vocal inflections to spice up the song. The added instrumentation like in this bit and the clapping of the hands are all reminiscent of the energetic Qawwali.

In true Manna Dey fashion, the song packs in comedic elements like when Abraham sings the words lapak-jhapak separately and then together or when he plays around with the phrase pani laa tu which translates to ‘bring we water.’ He treats the word paani as the two melodic syllables Pa and Ni (akin to the western So and Ti). He plays with it for a bit before inserting Laa and Tu meaning Bring and You. But instead of treating it like words, he treats them like melodic syllables. One wonders if Manna Dey, just as most Bengalis, was influenced by the nonsense poetry of Sukumar Ray which often turned language on its head. These techniques emphasise rhythm, break the typical classical structure and add, well, a bit of fun — toe tapping action. And as did Tansen, our prisoners bring the skies to its knees — it begins to rain. The prisoners felt respite that day.

Pt. Rajendra Gangani, one of the torchbearers of the Jaipur gharana of Kathak, brings the rains to the stage. In this iconic section of his repertoire he mimics the sound of the rain by using his ghungroos or ankle bells. Through his body we experience torrential rain, a light pitter patter and the most controlled drizzle. The pinnacle of this piece is reached when Ganganiji uses a single ghungroo to mimic the sound of a single droplet of rain. Incredible! A moment of complete control yet complete abandon. It establishes an age-old aesthetic and sensibility — when it rains, we dance.

Bollywood has taught us no differently. Enter — rain dances.

Rain, the time for dance

You thought of Aishwarya Rai Bacchan didn’t you? Atop a boulder while the clouds cry over her dancing body in Barso Re from Guru. Or maybe you think of her in white, dancing through the Chamba Valley in Himachal Pradesh in Taal se Taal Mila from Taal. What is it about Aishwarya Rai Bacchan’s dancing that makes her the perfect choice for rain dances?

Aishwarya Rai Bacchan is trained in both classical dance and music. The system for learning these forms are strenuous and expect the student's trust, abandon and hard work. The rain asks for the same. Saroj Khan, read: the master of Bollywood choreography, worked on both Barso Re and Taal Se Taal Mila. The two choreographies are wildly different. While Barso Re captures movements in abandon and joy through more natural expressions, Taal Se Taal Mila uses a lot more angular choreography to complement the mood. Khan’s choreography changes on the basis of music, context as well as picturisation. Aishwarya is joined by two other dancers in Taal which expands the kind of pictures that can be created. Her alone, simply interacting with the rain and her environment in Barso Re creates a different aura.

If seen as standalone pieces, separate from the film, just the dance itself can establish the personality of Bacchan’s two characters in the film. In Barso Re she becomes the quintessential Manic Pixie Dream Girl — a whimsical woman who lives in her own world. In Taal Se Taal Mila she seems to be more reserved, enjoying the rain in a gentler fashion.

Aishwarya Rai’s dance quality has the freedom required to show up on camera even in heavy rain. She has a body flexible enough to let go and yet still remain in control. But above all is her ability to translate emotion straight into her body. The most phenomenal moments in both songs happen in wide shots. If Madhuri is the queen of the closeup, Ash is definitely the master of wide.

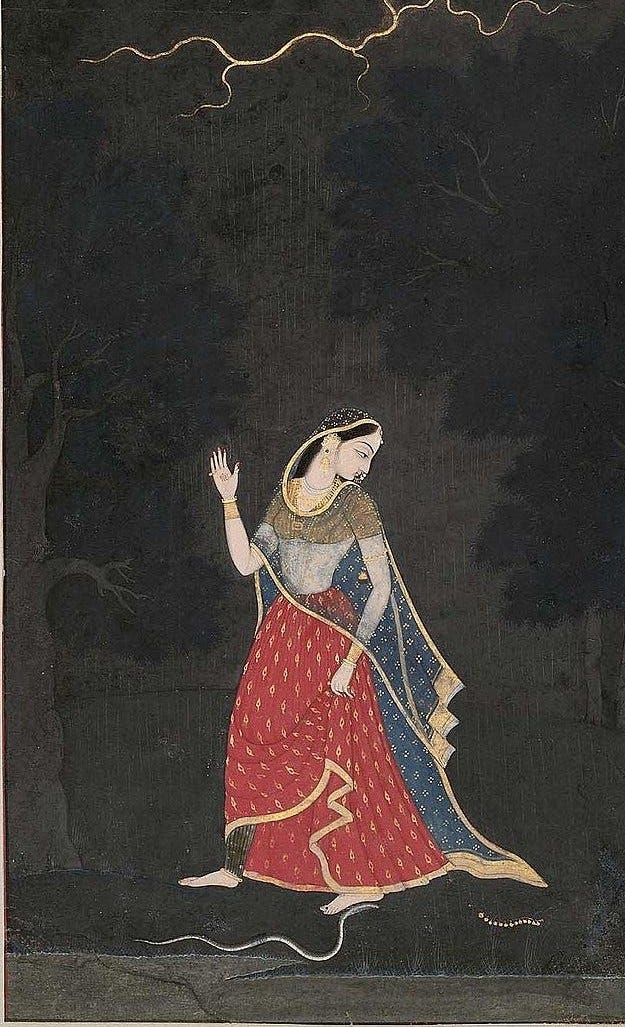

“Aaye baadara” Pt. Briju Maharaj sings as he sits, feet covered by a shawl, and embodies the character of a young girl looking at the rain clouds outside her window. He repeats the lines several times as he opens the window, looks at the clouds, compares them to her long, wavy hair and the smoke billowing out of the oil lamp. He sings the line again and again but this time with longing as he depicts the girl dreaming of Krishna embracing her. Afterall, the monsoons are the time for union.

Rain, the time for love

Imagine this: a girl, dancing in the rain. Freely, joyfully, the most beautiful version of herself. A boy, looking on in admiration. She increases the stakes for she is now joined by children and her blue chiffon salwar kameez is wet and clinging to her body. “Oh boy, that is the mother of my children,” — is exactly what everyone thinks when they watch the rain sequence from Dil Toh Pagal Hai. Young and dashing Shah Rukh Khan in a wet see-through, lemon-green shirt dancing with the queen of queens, my favourite, Madhuri Dixit. I have for several essays now tried not to talk about her or write about her. But I just couldn’t resist this one. I mean she’s wearing pomegranate pink lipstick, man.

Koi Ladki Hai or as the rest of the world knows it Chak Dhoom Dhoom forgoes cliche. It begins with Shah Rukh Khan, the young brute, beginning to dance with a group of children at an abandoned shelter — several ovaries were lost that day. Madhuri looks on as he sings about her beautiful smile and how that smile alone makes it rain. Tsk tsk, if only Tansen knew, if only.

Shah Rukh is not known for his dance moves but in this song he matches Madhuri’s every step. The choreography is simple and it should be. The mood is that of celebrating in the rain. The allure of the 90s dance song is in three simple things: one, effort, from the actor, the choreographer and the director. Dance songs became the beating heart of the films of the era, they needed to breathe on their own, outside of the context of the film, this one was no different. Second, replicability. Audiences needed to be able to pick up at least one step from the whole 6 minutes of run time and if it involved a pelvic thrust, even better. That would be enough for the song to sneak into living rooms and wedding halls. And three, a catchy tune. Chak Dhoom Dhoom has repetitive melodies but the change in steps, background, and the sheer conviction of the actors is enough to make us watch all of it.

Chak Dhoom Dhoom is not just a song about these two lovebirds though. In the middle of the song we move out of the abandoned shelter and land up in front of a hospital. Injured Karishma Kapoor is wheeled out of her ward and is surprised by her friends — the group of children, Khan and Dixit are dressed and ready to perform. The rain, the music and the joy from being pleasantly surprised overcomes Kapoor and she joins in making the rain the perfect backdrop for romantic love, yes, but also for friendship, all packed into 6 minutes of runtime.

And so we return to Tansen on that fateful evening when he made the clouds burst. Rain, the torrential, the light, the cooling, the humidifying, creates sentimentality. The kind that art relies on to flourish, bloom and shower down on all its admirers. With menshinkai bhajjis on hand and the smell of wet mud wafting through the windows, here is my attempt at cracking my creative block and letting it rain.

Raag Malhar is a family of Hindustani Classical raags which are based on the monsoon season. Some of its most well known derivatives are Raag Megh Malhar, Miyan ki Malhar, Gaud Malhar, etc.

Sangeet Samrat is a title that would be honoured upon the musical maestro at court.

Teentaal is a rhythmic cycle of sixteen beats. It can also be understood as a 4/4 structure of rhythm.

Qawwali is a form of devotional music that originates in the Sufi shrines of India and Pakistan. It is usually presented by a large group of performers which include vocalists, percussionists, harmonium players and an orchestra of background singers.

Video Sources: YouTube/Zee Music Classic, YouTube/90s Gaane, YouTube/SonyMusicIndiaVEVO

I love this, Eshna! I had never even heard of Pandit Rajendra Gangani before, but that single clip of him depicting rain through his body movements gave me goosebumps.

"Aishwarya for wide shots, Madhuri for close-ups": the thought had never occurred to me before but the moment I read it, I was nodding along. A brilliant observation!

Refreshing read. Definitely deserves a playlist.